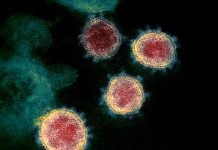

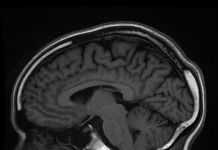

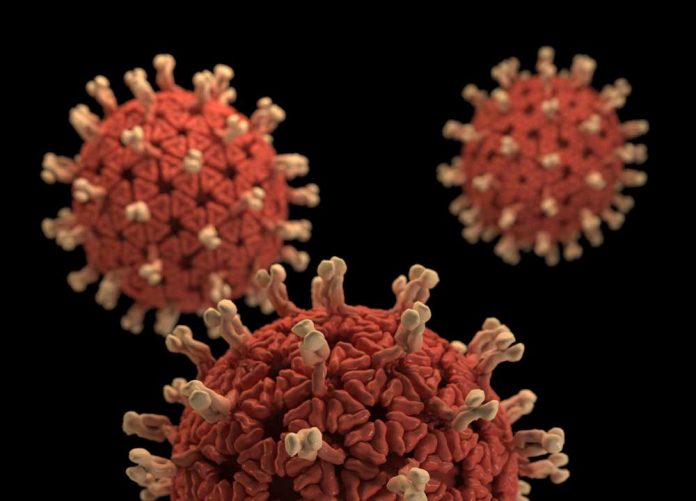

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses belonging to coronaviridae family. These viruses display remarkably high rates of errors during replication due to lack of proofreading nuclease activity of their polymerases. In other organisms, the replication errors are corrected but the coronaviruses lack this ability. As a result, replication errors in coronaviruses remain uncorrected and accumulate which in turn act as source of variation and adaptation in these viruses. Thus, it has always been nature of things for the coronaviruses to undergo mutation in their genomes at extremely high rates; more the transmission, more replication errors happen and hence more mutations in the genome leading to more variants consequently.

Obviously, changing to new variants is not new to coronaviruses. Human coronaviruses have been building up mutations to new forms in the recent history. There were several variants responsible for various epidemics since 1966, when the first episode was recorded.

The SARS-CoV was the first lethal variant that caused coronavirus epidemic in Guangdong Province of China in 2002. MERS-CoV was the next important variant that caused epidemic in Saudi Arabia in 2012.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the variant responsible for the current COVID-19 pandemic that started in December 2019 in Wuhan, China and subsequently spread worldwide to become the first coronavirus pandemic in the human history, has continuously undergone further adaptation accumulating mutations in different geographical regions giving rise to several sub-variants. These sub-variants have minor differences in their genome and the spike proteins and show differences in their transmission rate, virulence and immune escape infectivity.

Based on the threat that these sub-variants pose, they are grouped into three categories – Variants of concern (VOC), Variants of interest or Variants under investigation (VOI) and Variants under monitoring. This grouping of sub-variants is based on evidences related to transmissibility, immunity and severity of infection.

- Variants of concern (VOC)

The variants of concern (VOC) have clear association with the increase in transmissibility or virulence or decrease in effectiveness of any public health measures such as effectiveness of vaccines that currently in use.

| WHO label | Lineages | Country first detected (community) | Year and month first detected |

| Alpha | B.1.1.7 | United Kingdom | September 2020 |

| Beta | B.1.351 | South Africa | September 2020 |

| Gamma | P.1 | Brazil | December 2020 |

| Delta | B.1.617.2 | India | December 2020 |

- Variants of interest or Variants under investigation (VOI)

The variants of interest or variants under investigation (VOI) are known to have genetic changes that can affect its transmissibility, virulence or effectiveness of public health measures and are identified to cause significant community transmission.

| WHO label | Lineages | Country first detected (community) | Year and month first detected |

| Eta | B.1.525 | Nigeria | December 2020 |

| Iota | B.1.526 | USA | November 2020 |

| Kappa | B.1.617.1 | India | December 2020 |

| Lambda | C.37 | Peru | December 2020 |

- Variants under monitoring

Variants under monitoring are detected as signals and there is indication that they may have properties similar to a VOC but the evidence may be weak. Hence, these variants are constantly monitored for any change.

| WHO label | Lineages | Country first detected (community) | Year and month first detected |

| B.1.617.3 | India | February 2021 | |

| A.23.1+E484K | United Kingdom | December 2020 | |

| Lambda | C.37 | Peru | December 2020 |

| B.1.351+P384L | South Africa | December 2020 | |

| B.1.1.7+L452R | United Kingdom | January 2021 | |

| B.1.1.7+S494P | United Kingdom | January 2021 | |

| C.36+L452R | Egypt | December 2020 | |

| AT.1 | Russia | January 2021 | |

| Iota | B.1.526 | USA | December 2020 |

| Zeta | P.2 | Brazil | January 2021 |

| AV.1 | United Kingdom | March 2021 | |

| P.1+P681H | Italy | February 2021 | |

| B.1.671.2 + K417N | United Kingdom | June 2021 |

This grouping is dynamic meaning the sub-variants may be removed from one group or included in any group depending upon the change in assessment of threats in terms of transmissibility, immunity and infection severity.

Ironically, evolution of SAR-CoV-2 currently seems to be ongoing process. Going by the nature of this virus, so long there is transmission among humans there will be replication errors and mutations. Some mutant or variant may overcome the selection pressure to become more infectious and virulent or escape immune response to make vaccine less effective. Possibly, many more variants will be detected in due course in the regions of higher transmission. Minimising transmission and constant monitoring are the key to containment strategies.

***

Sources:

- Prasad U., 2021. New Strains of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus responsible for COVID-19): Could ‘Neutralising Antibodies’ Approach be Answer to Rapid Mutation? Scientific European. Posted 23 December 2020. Available online at http://scientificeuropean.co.uk/medicine/new-strains-of-sars-cov-2-the-virus-responsible-for-covid-19-could-neutralising-antibodies-approach-be-answer-to-rapid-mutation/

- WHO, 2021. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. Available online at https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

- ECDPC 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 8 July 2021. Available online at https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern

***